Desmids

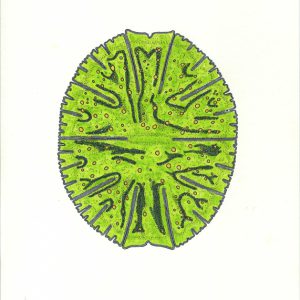

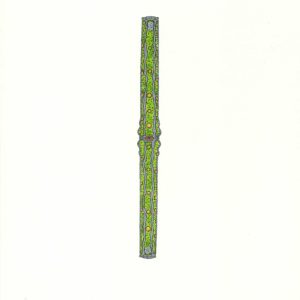

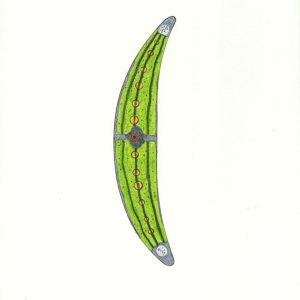

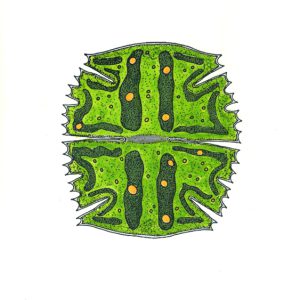

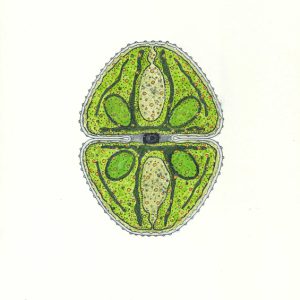

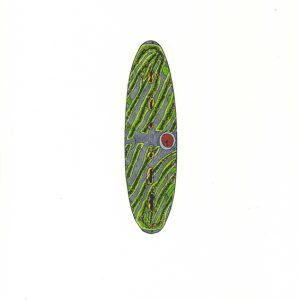

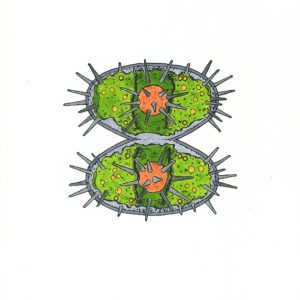

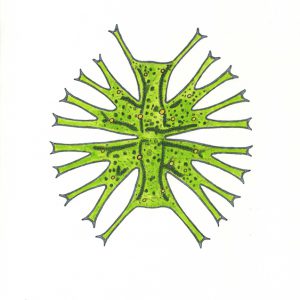

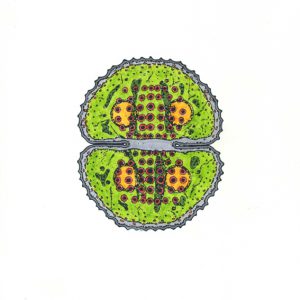

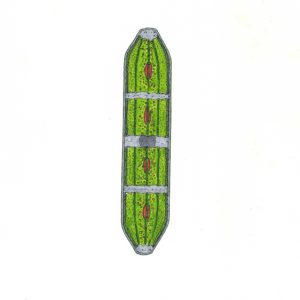

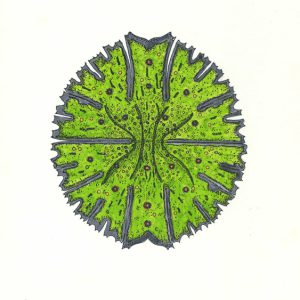

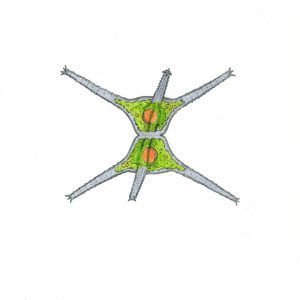

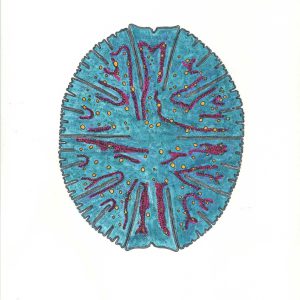

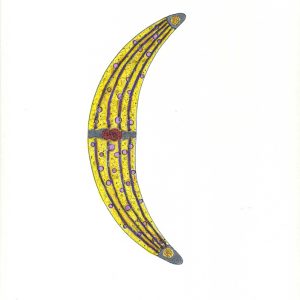

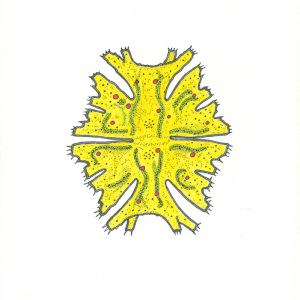

Desmids is the English technical term for a highly diverse group of unicellular microalgae, known in German as Zieralgen (ornamental algae), which occur exclusively in freshwater (approximately 5,000 species). Desmids are closely related to land plants. The species in this algal group are strictly symmetrical in shape: in many of them, up to three planes of symmetry (x, y, and z) can be identified, which likely accounts for the immense aesthetic appeal of these organisms.

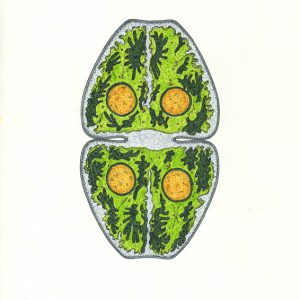

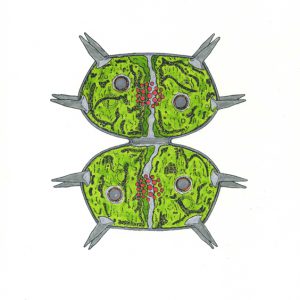

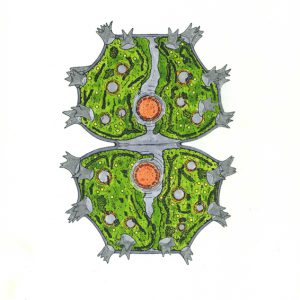

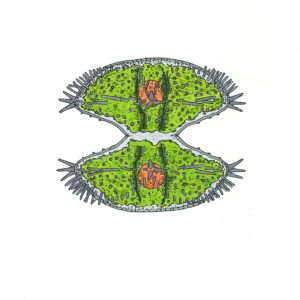

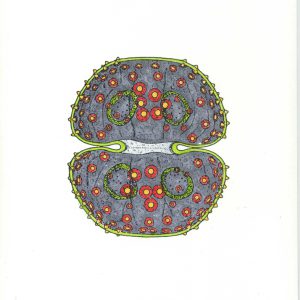

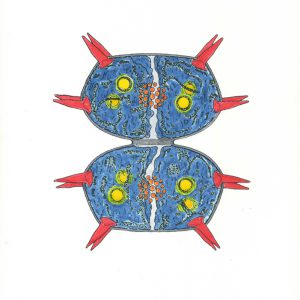

Desmids always consist of two equally sized semicells, each containing a grass-green chloroplast. The semicells are usually connected by an isthmus, in whose region the centrally located nucleus is also found. Desmids reproduce both asexually through cell division and sexually through a special form of reproduction in which two nuclei fuse via a cytoplasmic bridge to form a fertilized egg cell, without the prior formation of motile gametes. This zygote then undergoes meiosis and can survive long periods of unfavorable conditions, until cells with a single set of chromosomes emerge and initiate a new cycle.

Most species are capable of active, phototactic movement by crawling along a substrate. They achieve this by secreting mucilage through specialized pores in the cell wall.

Desmids inhabit rather nutrient-poor biotopes with pH values between 5 and 8 and therefore frequently occur in bogs. At the same time, desmids are excellent indicator organisms for the acidity and trophic status of a body of water.

In a number of genera (Cosmarium, Xanthidium, Staurastrum), the cell wall of certain species is specifically sculptured with warts, spines, and thorns. These structures often aggregate into ornament-like patterns whose function and origin are completely unclear, but which further enhance the aesthetic appeal of these organisms. The following hypotheses have been proposed for the formation of these structures: (1) the ornamentation serves to reinforce the cell wall; (2) it provides protection against predation; (3) its occurrence and formation are causally linked to the pore systems located in close proximity. Upon closer inspection, however, all three hypotheses leave questions unanswered—above all, the specific nature of these structures remains unexplained.

Thus, the question also remains unresolved as to what evolutionary advantage something that appears—at first glance—so useless as ornamentation or beauty (which, of course, exists solely in the eye of the human observer) could possibly have in evolution. Although clearly phrased in anthropocentric terms, it is therefore not entirely far-fetched to hypothesize that the particular symmetry relationships of the cells and their ornamentation represent a preadaptation to the human sense of beauty, so that the curious human gaze may take interest and pleasure in them and perhaps protect or preserve the species. In a certain sense, this is already happening, since desmids—like some other groups of organisms—are now being successfully cultivated on a large scale in several laboratories around the world, meaning that their genes are being multiplied and spread much more widely.

Through an artistic reinterpretation of various forms on paper, using in part unnatural colors, not only is the fantastic diversity of forms within this group of organisms revealed, but the great aesthetic potential of these organisms also becomes apparent—indeed, it is made visible, and the species attain a sense of sublimity. This once again demonstrates that aesthetics or beauty can indeed represent a fixed parameter in evolution, precisely because nature itself is also an artist.